How do I remember my Dad?

I remember him as a man of peace

who fought to separate fights

So that everyone could live in harmony,

one with his neighbour.

How do I remember my father?

I remember him as one who did

not joke with the welfare of his children. He weathered

the storms of life so that they could have

a less difficult existence. He risked the perilous

Atlantic that I may later hover over it without fear.

How do I remember my father?

I remember him as a philanthropist

whose kind gestures have continued

to open doors for his children

wherever they go.

How do I remember my father?

I remember him as a teacher of virtues

through exemplary living. He was my counsellor;

his wise counsels which I have followed

have brought no regrets.

How do I remember my father?

He would rather endure his pains than seek revenge

to prove he was in the right.

Daddy was rich without being materialistic.

Moderation was his compass for life.

He did not care for the things of the world;

Houses, cars and fame, none could move him.

He was kind without being weak.

He was loving without being indulgent.

He has, through his life, left indelible marks

on the sands of time.

He is forever in our hearts.

Eyoh Etim, PhD.

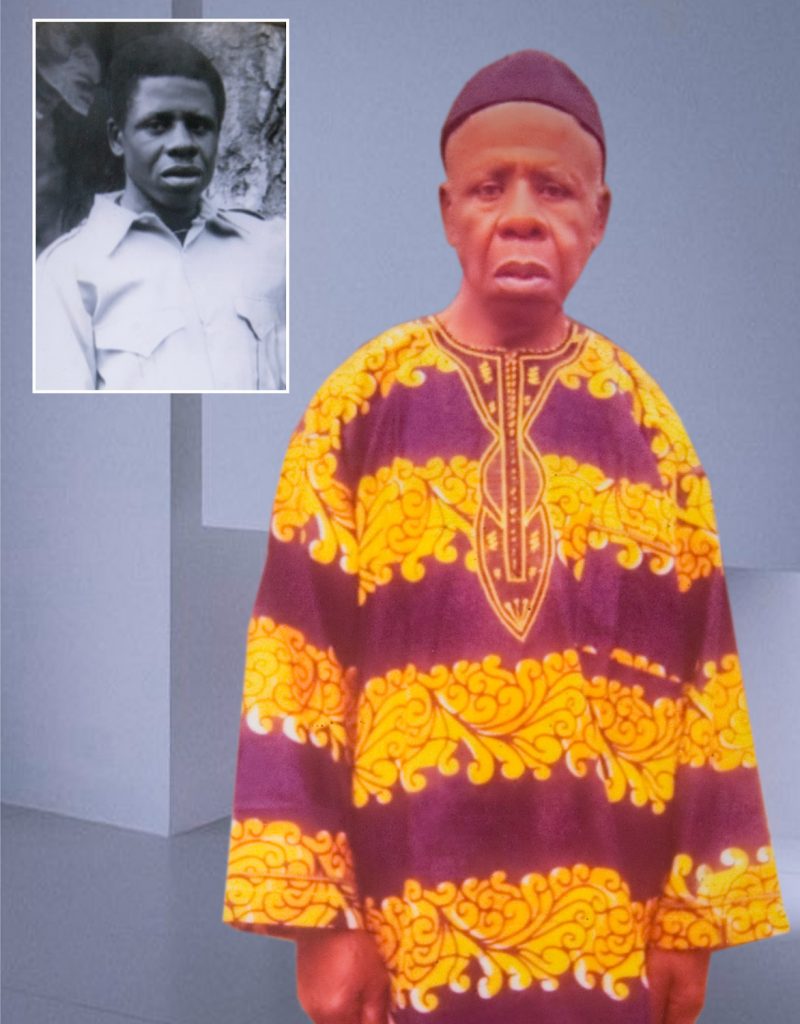

My father, Chief Asuquo Etim Effiong, joined his ancestors on the morning of Thursday, 7th of July, 2022. I remember vividly that I was lecturing 200 level students in the University that fateful morning when a call came in from my younger brother. Immediately I saw the call, I knew intuitively that the fated event had finally occurred. I excused myself from class and went outside. Dad had been fading away from us and each time a call came in I needed to take it to get an update on his health. When my brother asked if I was busy, if I was in school and if I needed a more convenient time to talk, it suddenly dawned on me that the worst had happened. I told him he could speak. I was then informed that my Dad was no more with us. As I had said, Dad had been fading away from us for some time and we had known that the inevitable event was no longer far away. But he had stayed strong enough to meet all his children, far and near, and had blessed us with his dying breath and strength. Yet I was never prepared for the eventuality so related that day. I was devastated inside. The ground under my feet had shifted, my world had changed. I have lost one of the persons that had given my life some form of stability. I had just lost my counsellor, my teacher, my motivator and my inspiration; I mean the very one who had given me the foundation and what it took to make me stand before young intellectuals and lecture them on of the most enduring academic subjects on the earth. Yet he himself never went to school. But he had a vision to encourage me to go to school because he saw tomorrow yesterday. He knew that the world in which he lived and worked had changed and if his children must survive, they had to be educated to experience the paradigm shift.

As I went back to class, I felt a kind of inexplicable peace surrounding my soul and calming my spirit, even as I was crying inside. I knew right then that my Dad was right there comforting and preventing me from crying and disrupting my lecture. With this strength, I was able to complete my lectures that day with the gusto and courage that was nothing but divine. Then I could go home and cry all I could, for heroes do not weep in public for the anguish and pleasure of both friends and foes, respectively.

I knew that my Dad was old, quite old. What, however, I did not reckon was the number of years until my elder brother schooled me on not only the possibility, but also the fact that Dad was over a hundred years old. The man never used a walking stick nor bent in any way. Old breed, that man. The last of the strong breed. But he is gone now and leaves behind only the memories that we have of him, for we become memories to our families, friends and loved ones after we have gone. The lesson then is to make the best memories while we are here with as many that come our way.

Before I proceed, I need to state that my father did not go to school. In fact, both my parents did not have formal education. Growing up, I was never proud of that fact. In school, I had some friends whose parents were teachers who spoke and wrote in English, the linguistic gold and code of the time. I usually felt ashamed to talk about my parents in their midst or show them off up until in recent years. Perhaps, this social discomfort has been the unconscious drive in my pursuit of education at all cost and by all means possible, for I did not want to do anything but be educated. I wanted to be so educated that it made up for my parents’ lack of formal education. I did not mind the difficulty, the lack and the pains of loneliness and want. I did not care about the isolation, the psychological burden of perpetual dissatisfaction. Education, if and when attained, could succour them all. Then one step after the other and we are here today.

I am the son of a petty trader and a fisherman who, by the special grace of God, became a PhD. Sometimes what motivate us to win are the things that were meant to keep us down. Whether we win or not is dependent on our attitude to the challenges we face. We can either sink in or ride on the storm. In our dark moments, we may have fears, and I had my fair share of fears too. In fact, navigating my way through the path of life and academic success meant that I should face my fears and act in spite of them, just like the great men and women in history had done – Hector, Napoleon, Cleopatra, Caesar, Mary Slessor, Ojukwu and Obama. I had this morbid fear while an undergraduate that my Dad would die and, with it, my dream of having an education. Most times the realisation of our dreams is tied to the existence of others, especially to persons whose influence towers over our lives. That time he was still in Cameroon and the place was fraught with dangers – the brutality of the Cameroonian gendarmes and the conflict between Nigeria and Cameroon over the Bakassi Peninsula. The sea was yet another source of danger: that monster claimed so many lives and nealrly took mine on one occasion. How Dad survived the sea through those many years remains a mystery.

But Dad had retired to Nigeria safely around 2012 and lived out the remainder of his days in peace and tranquility. I pressed on and overcame my fears, completed my education, all my formal education before his demise. It is as if Dad had read my fears and had said, ‘Son, go on, get all the education you need. I will hang on until you’re done’. He didn’t see the fruits; the car(s) never came, at least not yet, he did not see the houses, he did not see the wife and the children. But he had dreamed them all for me and knew that they were there in the package of the vision and will materialise at the appropriate time. Dad always saw it ahead of me and this time around I cannot doubt as I rest my belief on the evidence of former visions.

So how do I remember my Dad? How should I remember him? I will remember him in inks and hymns preserved for posterity. I will remember him by helping as many people as it is possible to shine the light of education through positive impacts. It is one of the reasons I began this website in August 2020 in the heart and heat of Covid-19 when the need for online learning and sourcing for educational materials became more apparent. Between then and now, the site boasts of over 70 posts which have left the postcolonial pessimists and postmodern Thomases wondering at the possibility of one person producing all of them. The answer lies in hard work, diligence, dedication, perseverance and commitment. The website is a sign of my commitment to sharing knowledge, getting young people to read and love literature, and creating positive impact beyond my immediate environment.

Shortly, after my Dad passed away, I had an ugly experience with the website, betrayed by the person I trusted to administer it. I asked myself what Dad would have done if he were in the same frustrating situation that I was put in then. The answer I got was that Dad would not seek revenge; he would pick the pieces of his life and move on. This he had done in all the cases of injustice he was exposed to all through his life. He never sought revenge. He would leave justice to the only One who is just. I thought this was a sign of weakness but, reflectively, I’ve come to see it as a sign of inner spiritual strength. Websites are attacked all the time, but it is heartrending if it is attacked by the very people you trust with the responsibility of running it, the very people you want to benefit from its content and the very people who should be encouraging you to write. The experience also taught me to better appreciate the dangers that lurk around the field of cultural production, the unpredictable pattern of human nature and the need to watch closely those closest to you.

Since Dad’s demise, I have thought of how best to write an essay that would reflect that my life revolves around his existence. The idea never came until I thought aloud on the very issue. I suddenly asked myself on the afternoon that I began this writeup, ‘How Do I Remember my Dad?’ And the question itself birthed the topic of the essay; the idea that it should be a poem and an essay of remembrances. ‘In Memoriam A.H.H’ was written by Alffred Lord Tennyson around 1850 to memorialise his dear friend, Arthur Henry Hallam. I parody Tennyson’s title in the remembrance of my Dad, who was equally my friend.

The earliest recollection I have about my Dad goes back to childhood. I had a normal but privileged childhood but I was, indeed, a child; innocent or even naïve. For instance, I believed that the masquerades were actually ghosts. Of course, they are! Do not get me wrong! I also believed that seeds swallowed could grow out of the unfortunate child’s stomach. When I grew a bit older and knew the facts, I played this prank on my immediate younger sister and she cried hell all through that day. I am sad now remembering how she wailed about what would become of her when the udara seeds she had swallowed would grow out of her stomach.

In terms of discipline, Dad was gentler than my mother. In fact, Dad always rescued us from the grips of Mum’s disciplinary measures. But I remember this particularly harsh disciplinary measure that Dad meted out to me once when I was a very young child. The incident happened in the village, Ekpene Ukim. I recall that I had just finished gorging on a meal of coconut rice one afternoon. I had also taken enough after-meal water so that my stomach was as round as the world-cup/Olympic soccer ball. Dad was seated outside in his easy chair – the foldable type made of tough cloth and wood. He called me and sent me to fetch a cup of water. In my naivety, I took a sip of the water, a love sip as I would imagine then, and he noticed it. He asked me to drink all the water in the cup as punishment for drinking the water that was meant for him. Recall that I had just eaten and a heavy meal at that – you see, for Mum, being well-fed meant eating till your stomach confesses on its own. I had also drunk water before now. I could not finish the water in the punishment cup and was saved by mother’s intervention. I learnt my lesson from that day. But reflecting on it, I still think it was harsh, too harsh for a child, too harsh even for the child born in the 80s. It was also harsh judging from the principles of infantism! But this was how parents taught children certain life lessons in the 80s. Especially manners!

Apart from the foregoing, Dad was a joy to live with – ever caring, always sacrificing and ever willing to help. He made the welfare of his children a priority. Dad encouraged all his children to go to school and supported us the best way he could with the little he had.

I remember the life he lived in Bekumu, Cameroon, the life of burning himself, literally, to prepare fish for sale so that he could feed his family. Even now I could imagine him bending over the heated fish barn, all smoke and fire, soaked in sweats generated by the hellish heat, carefully watching the fish in their sticks, turning each stick at the appropriate time lest it burned and all the cost and effort lost. My ayebutter eyes could not stand the slap of the smoke, hence I always found myself a good distance from the smoky and hellish barn. Dad would ask me to go to bed while he stayed up late into the night until the fish is well roasted. He did this daily for over countless number of years. He, however, pushed me benignly away from the hard labour that he did. He pushed me to go to school. He loved me enough not to want such a life for me. My Dad was sacrifice personified. I could not count the number of times I pestered him to let me join the other fishermen to sea. He gently refused and gestured me towards the corridors of education. I remember once when I was on a holiday visit to Dad in Cameroon, when one of the fishermen approached him to let me have a taste of the sea, he refused even when I was interested in trying the experience. He knew that the sea was not as romantic and profitable as the man had painted it to be. It might have been profitable but it had its own perils which outweighed the profits. Dad had a vision and saw the future of work.

He is gone now, leaving only memories, memories from which we can learn. I mourn for him everyday because he saw the vision but missed the fruits. This is the only tragedy that I perceive in his demise. However, I am certain that he is happy wherever he is knowing that the vision lives and illuminates the world where he has left after many years of existential struggles.

My Dad will be laid to rest on Saturday, the 10th of December, 2022. The funeral service which will be conducted by the Sanctified Mount Zion Church, Ekpene Ukim District Headquaters, will hold at the St Thomas’ R.C.M School, Ekpene Ukim in Uruan Local Government Area. I invite you all to be there to sympathise, comfort and support us as we pay our father the last rites of respect. I hope to see you there.

In the spirit of Men’s Day, let me celebrate a brave man, a real man, a hero who crossed many seas and lived to tell the story. Farewell, Dad. May posterity look on you more kindly than life had done.

Reading through this essay, I empathize with you the more, Dr.

We share alot in common, sir. I was born in Bekumu, Cameroon.

Farewell, Papa!

Farewell, Chief. Rest in the peace you richly deserve.

Dear Dr Eyoh Etim, please accept my condolences.

Death is the terminus of every mortal.May the Lord grant his soul an eternal repose

Farewell, my friend’s father. May the light of God lead you home.

Accept my heartwarming condolences, please.

This is so full of memories that will remain evergreen in our heart.

I sympathize with you, Dr. over the death of your dad.

Keep abiding to his footprints, Dr

Rest on Hero.