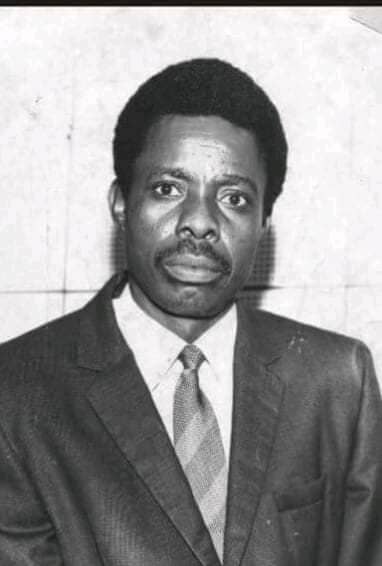

Author’s Background: Etim Uyah Akaduh was born on 27th April, 1929 in Eyufuo Oruko in the present Urue Offong/Oruko Local Government Area, Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria. He had his early education in Methodist Boys’ High School, Oron, where he sat and obtained his Senior Cambridge Certificate with exemption from London Matriculation owing to his brilliant performance. He graduated in Mass Communication at the University of Lagos, Nigeria, and worked at conglomerate multinationals, the United African Company (UACN), Nigeria Marine and Nigeria Broadcasting Corporation (NBC), now Federal Radio Corporation of Nigeria (FRCN).

In 1954, he was among few Nigerians to be enrolled for training on Radio Broadcasting at the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC). While in London, he participated in a literary competition held throughout the then British West Africa. His poem on advertising a beer ‘Begerdof’ won him a prize for Nigeria. In 1955, his short story on the legendary Okpo Obribong entitled ‘Birds carry Oro Man to Heaven’ won him another prize in the Nigeria Broadcasting Corporation Christmas Short Story Competition.

The string of his successes followed when Franklin Book Programme of America recognised his aptitude for writing and sponsored him for writers’ workshop at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. His international media work alongside his professional friends, Marshall Howard Wright and Senator Edward Kennedy, were recognised for studies in few Media institutions in Canada and United States of America. During the succeeding years, Etim Uyah Akaduh’s poems, literary reviews, articles and short stories gained recognition both nationally and internationally. He also made a few TV criticisms, one of which was a review of Cyprian Ekwensi’s Old Man and the Forest in the West African Pilot Newspaper. Etim Akaduh and Professor Wole Soyinka jointly provided the technical and artistic inputs which saw to the earliest broadcast of Soyinka’s The Swamp Dwellers.

He retired from NBC as External Studio Manager in 1974, and later served as Member State Scholarship Board of the defunct Cross River State in the seventies. He was a publisher, educationist, broadcaster and author of various literary works which include;

1. The Clever Monkey (folktale and fables)-1981

2. English Efik Dictionary (co-authored)-1981

3. The Magic Box – 1982

4. The Ancestor (a Novel based on Ekpu Carving)-1983

5. Fedemina (Oro folklores)-1985

6. Nsini Oro (Oro autography & Mini Dictionary (1991)

7. Okuiku Nwid Oro-1991

8. My Classmates (anthology of poetry) -1993.

He died on 29th October, 1994 (Source: Manson Publishing Company).

Background to the Novel:The Ancestor is a postcolonial novel that depicts the neocolonial realities in post-independence Nigeria, as experienced by the people of Oron in Akwa Ibom State. It portrays Biaksaň community at its moment of cultural crisis; when the colonial culture competes with the precolonial cultural ethos of the people, throwing up hitherto unknown maladies like greed, deceit, envy and jealousy, poor leadership and, consequently, underdevelopment seen in terms of the living condition of the Oro people in Biaksaň community, which is more or less a microcosm of Nigeria and Africa. The novel equally emphasises the need for Africans to hold on to their cultural values even in the face of attacks by the new culture, as well as facing reality and knowing that there are certain lessons that must be learnt from the new culture in order to move society forward. In discussing such themes as precolonial and postcolonial realities in the Oro society, Etim Akaduh’s The Ancestor compares with Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart and Ayi Kwei Armah’s Two Thousand Seasons. The long title of the novel is The Ancestor (a novel depicting life in rural society).

Plot and Plot Summary: The novel has a non-chronological plot structure, as the story begins in medias res. The protagonist of the novel, Tisoň, has just returned to the village after 25 years of studies abroad, where he had earned a PhD in one of Humanities’ courses, likely Anthropology or Sociology. Everyone is afraid that Tisoň would have forgotten the culture of his people having been exposed to a foreign culture for so long. But Tisoň proves everyone wrong in the manner in which he conducts himself during the reception ceremony organised for him in the village. He does not only speak the language of the people, he also remembers the rites and traditions of the various cultural institutions of the people; the Ekpe chants, the dance steps of the Ekpe society, the songs and other aspects of the people’s culture. Tisoň had also married among his people; one of the reasons he is accepted by the people who had feared that he would take a white woman for a wife.

Tisoň returns to meet his community Biaksaň in a state of postcolonial disillusionment; the new black leaders are depicted as dishonest politicians who lie to the people during every election period. There is poverty and underdevelopment everywhere one turns in Biaksaň and this reduces the humanity of the people. Tisoň is expected to step in and show proper leadership but he wants to start off through the cultural route, and that is by making the people have renewed faith in themselves and in their precolonial cultural values which are now extinct or have been appropriated by the greedy leaders.

Tisoň’s major project is to write a book about the precolonial culture of the Oro people but he wants to do this by studying the family’s most prized artwork, Sinue, also known as the Ancestor from which the title of the novel is derived. Tisoň’s father having passed away, the artwork and the other properties of the family are now in the custody of his uncle, Ekuň, now the oldest member of the family. The major conflict in the novel is built around this artwork which pitches Tisoň against his uncle; for when Tisoň demands to see the Ancestor, Ekuň lies that it has been stolen or lost alongside other family carvings which he had buried at the creeks when the government was hunting for artworks in all the communities. Tisoň is angry with his uncle for being careless with the most valued art object in the family and, in his anger, utters abominable words that impugn the dignity and integrity of his uncle. Insult to an elderly person is never taken lightly in Africa’s cultural space and the destruction of one’s reputation is a matter of life and death as people were seen to survive mainly by their reputation and good name.

Tisoň had made a disparaging remark about Uncle Ekuň’s birth and morality and the old man, well known for his short temper, is ready to go all the way to defend his name. It appears that Ekuň does not trust the intentions of Tisoň in seeking Sinue, the Ancestor, and decides to hide the carving from ‘The New Comer’. All the lower-level structures for resolving disputes are exhausted and the matter goes to the village council presided over by Ekim, the village head. In order to clear his name, Uncle Ekuň is ready to ritualistically chew the ekpese seeds, the poisonous bean seeds believed to kill the guilty and exonerate the innocent. All appeals to Ekuň not to endanger his life by chewing the seven poisonous seeds fall on deaf ears. He nearly dies from the venom of the seeds until Tisoň intervenes by administering an antidote.

In the end, the sought-after artwork is discovered with the help of Atidiaň, Tisoň’s aunt, who prevails upon or persuades Ekuň’s wife to reveal where her husband had buried Sinue. Sinue is unearthed and taken to the national museum and Tisoň is ready to begin his book project that will counter the hegemonic colonial discourse on Africa as a space that was without its culture and civilisation before the advent of the colonialism.

Subject Matter: The subject matter of Etim Akaduh’s The Ancestor is postcolonial disillusionment and the need for Africans to embrace their cultural values as a way of returning society to its stage of moral sanity. This is seen in the depiction of Biaksaň as a postcolonial space replete with poverty and underdevelopment whereby the people are disappointed with the post-independence leaders who lie to and exploit the people. Tisoň’s return marks the beginning of the search for solutions; he is well educated and highly equipped to lead the people out of their postcolonial quagmire but he wants to write a book to enlighten the people and the world at large that Africans had a glorious past that has been buried by hegemonic colonial discourses.

Setting: Akaduh’s Ancestor is set in postcolonial Nigeria years after independence. By the time the novel opens, the colonial masters had departed back to Europe and the nation had gained its independence from the British. Thus, Tisoň returns to a deeply disappointed society plagued by hunger, poverty and underdevelopment owing to poor leadership at all levels of society. The novel is specifically set in an Oron village called Biaksaň. Oron is a local government area in Akwa Ibom State in present Nigeria. The novel also depicts whatever is left of the precolonial cultural values of the people now seen to be under intense appropriation. Another place name in the novel is Ekwai village where a lawyer who had just returned from abroad was poisoned by a jealous villager. This incident happened ten years before Tisoň’s return.

Point of View: The Ancestor is written from the third person narrative point of view. This can be exemplified from the following excerpt about Ekuň: ‘As a teacher, Ekuň was accused of pushing the headmaster of the school into an empty drum, and the headmaster had sustained injuries on the head and the arms’ (10).

Themes: The Ancestor treats various themes, both major and minor ones. Among the major themes of the novel are the clash between precolonial and postcolonial cultural values of the Oro people, the communal spirit among Biaksaň people, poor leadership, neocolonialism, postcolonial realities in Nigeria, the value of education and educated leaders, the conflict between tradition and modernity, the need to value African culture and tradition against the background of colonialism. Other not so major themes in the novel include family bond, envy and jealousy of successful people, poverty, hunger, friendship, man and his reputation, anger as dangerous to man’s life, loss and restoration, family feud and reconciliation.

Characterisation: Among the major characters in the novel are Tisoň and Ekuň while the minor characters include Uwe, Mbia, Ekim, Abang, Atidiaň, Nwodiok the rainmaker and Nkansi.

Tisoň is the protagonist and hero of the novel. His name means ‘Father of the soil’. He is married with children and is well to do, as can be seen in his big car and quality lifestyle. He is called ‘the book of the village’ by an old man in acknowledgment of his high and quality education. He is a widely travelled and educated man who has been abroad for between 25 and 30 years. His learning and research have taken him to important places like Cairo, Morocco, Accra, Lome, Dualla, Kinsasa, London, Paris, New York, Tel Aviv and Toronto. One of the sterling attributes of Tisoň is that despite being exposed to western education and culture, he, upon his return, still cherishes his roots. His education, instead of keeping him apart from his culture, endears him to it. He wants to use his education to the advancement of his people especially in solving the problems of society.

Ekuň is Tisoň’s uncle. He is a former school teacher often given to anger which cost him his job. It should be noted that in African cosmology, names have both spiritual and symbolic significance in an individual’s life. Most of the names in the novel have meanings that reflect the character of the person. For instance, Ekuň means ‘war’ and this is seen in the fight-ready posture of the character. He is sensitive and proud which explains his reaction after Tisoň made insulting comments about him over the missing ‘sticks’ (carvings).

Mbia is Tisoň’s childhood friend. This name suggests that he likes to gossip as can be seen in some of the events in the novel. He is one of those who observe that western education has not succeeded in turning Tisoň’s head. He also offers to slaughter a goat to celebrate Tisoň’s homecoming.

Uwe is Ekuň’s first son, the same name that Tisoň’s second son bears as it is a family name. Names are sources of both personal and collective identity in the Oro culture and could be used to identify a person’s family. Uwe is mentioned when he is asked to come and greet Tisoň by his father, Ekuň.

Ekim is the village head of Biaksaň. His name suggests darkness, implying that he reigns over a dark clime, though he is not necessarily a bad leader himself.

Abang is so called because of his prowess in drinking palm wine. His name means ‘pot’.

Atidiaň is Tisoň’s father’s sister. She is instrumental to the discovery of the ‘lost’ carving, Sinue.

Nkansi is Tisoň’s childhood acquaintance who had long died in poverty before Tisoň’s return. Tisoň’s recollection of him is in the event in which he was wrongly accused of stealing a goat for which he took an oath to clear his name.

Language and Style: Akaduh’s Ancestor is written in postcolonial English, which is marked by appropriation, abrogation, glossing, transliteration and untranslatable language. It deploys songs, chants, proverbs and other materials drawn from the oral tradition of the Oro people. These are the aspects that stand this novel in the same category as Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart. The novel also deploys humour, irony, symbolism, ideophone and other stylistic tropes to send home its message on the transformation of society through cultural renaissance.

Simile is seen in the expression, ‘Where he [Tisoň] worked, many big people respected and obeyed him like a king’ (2). An old man says this about Tisoň as Tisoň goes around greeting people in the village after his return from abroad. The expression ‘big people’ is an instance of transliteration which means very important personalities in Oro language. An instance of glossing is seen in the expression ‘mmataň’ or the whites’ used in the larger expression: ‘In his own days many years back, he used to belong to such an exciting crowd, when they would storm a very important visitor, like mmataň or the whites’. Glossing refers to creative translation and this is seen in ‘mmataň or the whites’ where ‘mmataň’ is Oro for white people. The expression ‘the Captains of the Canoe’ is a metaphor which refers to the postcolonial leaders in Biaksaň and beyond. Ekuň, in making this statement, notes the negligence of the village by these neocolonial leaders who forget the people after lying to them to get votes every election year.

Humour is seen in how Unuň’s children buy their father clothes (four shirts) from Panya and force him to wear them against his will, as Unuň is not used to wearing clothes. One night, Unuň falls ill and accuses the shirt he is wearing of making him sick. The man gets well immediately the clothes are removed. This story, funny as it is, teaches a lesson in the power of the human mind.

Symbolism is built around Sinue, which is the symbol of African cultural heritage and civilisation. Sinue tells the story of Oro people, their origin which goes back to King Solomon, their royal lineages, their struggles, failures and triumphs and how they got to be where they are through years of migration. Tisoň’s character is equally symbolic as he represents the hybridity that characterises the postcolonial subject’s personality, among other meanings.

Irony is also seen in how Tisoň still loves African culture despite being exposed, for many years, to western culture and education.

Ideophone is seen in the expression ‘kpomfak! Kpomfak! Kpomfak!’ which is the sound of a drum in Biaksaň village (22). Another instance of ideophone is seen in the expression ‘Taam! Taam! Taam! Taam!’ which represents the sound of the Ekpe bell (24). Tisoň is a member of the Ekpe and Ekong societies whose rites he still remembers and participates in after spending years abroad. The sound of the long drum is represented in the novel as ‘Ton-ton-kim; ton-ton-kim’ (24).

Untranslatable language is seen in Tisoň’s Ekpe chants as follows: ‘Sua fi! Sua fi! . . . Sua fi!, Inokon! Sua fi Okpokpo! . . .’ (25). Another instance of untranslatable language is seen in the song led by Ekuň which goes thus:

Ekuň: Sira ntite osu, oo!

The Crowd: O, ooo

Ekuň: Ntite Osu, ooooo

The Crowd: Osu onyi uko asira ntite.

I would love to download the PDF format

So interesting reading about my late dad….wow

Great work. The new version of the book will soon be out.